This submission of the Women’s Rights Party of Aotearoa New Zealand is in response to the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill.1

Introduction

The Women’s Rights Party is a registered political party representing around 800 members, and focused on issues that directly impact women, girls, and children. As a registered political party, the Women’s Rights Party exists to maintain and protect women’s rights, including:

- The right to speak freely.

- The right to peaceful assembly, association, and movement.

- The right to safe single-sex spaces for women and girls.

- The right to be free from violence in all its forms.

- The right to protect and safeguard our children.

- The right for motherhood to be recognised as exclusively female.

- The right to fair play in sports.

- The right to use clear and plain language when referring to women in the media, academia, in healthcare, at work and at home.

We have analysed the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill and consider that the Bill in its current form threatens all these rights. We seek changes to the Bill for these reasons:

- The description of prohibited behaviours is not sufficiently precise and would capture a wide range of behaviours that are not connected with the harm targeted by the stated policy objective.

- The Bill needs to be more precise in the matters of actus reus and mens rea, so that it does not capture and criminalize gender critical views and speech.

- The use of the word “distress” in this legislation is problematic. It is a widely observed phenomenon of people who have adopted a gender identity inconsistent with their sex, that they often experience strong emotional reactions, including distress, when gender ideology is questioned in any way.

The Women’s Rights Party is generally supportive of legislation that will address and prevent harms associated with stalking and harassment. We recognise that stalking and harassment can be a form of coercion and control, often occurring after a relationship breakdown. It is typically sex-based in that it is usually perpetrated by a man and focussed on a woman who has been subjected by him to a pattern of

abusive behaviours over time, that can be physical or non physical, with the intention to hurt, humiliate, isolate, frighten, or threaten her in order to control or dominate her. In this context, fear, including the very real risk of violence, goes well beyond “distress” and may be directed not only at her, but also her children, others associated with her, or even her pets.

For this reason, we are unable to support this Bill until it is amended to make it clear that “distress” in the context of the current Bill does not include the distress that people may feel when their gender identity is questioned or is not affirmed.

The reasons for our position are set out below.

Submission

Point 1

Section 216O of the Amendment Bill defines stalking and harassment in this way:

(1) For the purposes of section 216Q, a person (person A) stalks and harasses another person (person B) if person A—

(a) engages in a pattern of behaviour that is directed at person B by doing any specified act to person B on at least 3 separate occasions within a period of 12 months; and

(b) engages in that pattern of behaviour knowing that it is likely to cause fear or distress to person B.

(2) To avoid doubt, the specified acts may be the same type of specified act on each separate occasion, or different types of specified acts.

The use of the word “distress” in this Bill is problematic, and the word is not sufficiently defined for use in this context.

When reading the title and the purpose of the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill, most members of the public would assume that the Bill is intended to capture only a small number of dangerous, harmful, and/or obsessed people. But in fact, the Bill as it is currently drafted with the word “distress” in it potentially captures and criminalises the majority of law-abiding New

Zealanders, simply for honest speech.2

The Merriam-Webster Legal Dictionary defines emotional distress as: A highly unpleasant emotional reaction (such as anguish, humiliation, or fury) which results from another’s conduct and for which damages may be sought.

It is a widely observed phenomenon that people who have adopted a gender identity that is inconsistent with their sex often experience strong emotional reactions when gender ideology is criticised or questioned in any way.

Unpleasant emotional reactions such as anguish, humiliation and fury are widely observed among this population when gender ideology is criticised or questioned, or when they are “misgendered”. These emotions all fit within the above definition of emotional distress.

People who don’t adhere to gender ideology would generally expect that the criticism or questioning of gender ideology is not dissimilar to the criticism or questioning of religious beliefs such as Christianity or Buddhism.

New Zealanders often criticise and question these religious beliefs in robust and repetitive ways and in a variety of settings. However, these criticisms rarely result in highly unpleasant emotional reactions such as anguish, humiliation and fury. It is unlikely that the Bill as it is drafted would ever result in stalking and harassment charges being laid against someone simply because they question or criticise Christianity or Buddhism.

However, in the special case of gender ideology, where a person has adopted a gender identity that is inconsistent with their sex, there is a high chance that Person A could cause Person B to feel “distress” inadvertently, unwittingly, or simply because Person B is unwilling or psychologically unable to tolerate opposing views.

Of particular concern to the Women’s Rights Party are situations where Person A could cause Person B “distress” because Person A is seeking to maintain or defend women’s rights, such as:

- The right to speak freely.

- The right to peaceful assembly, association, and movement.

- The right to safe single-sex spaces for women and girls.

- The right to be free from violence in all its forms.

- The right to protect and safeguard our children.

- The right for motherhood to be recognised as exclusively female.

- The right to fair play in sports.

- The right to use clear and plain language when referring to women in the media, academia, in healthcare, at work and at home.

The Bill needs to be amended so that it does not capture and criminalise people who are seeking to uphold these important rights, simply because they have caused some level of “distress”, whether knowingly or unknowingly (for example, in a social media post), to a person who has adopted a gender identity that is inconsistent with their sex.

Point 2

Section 216O of the Amendment Bill says:

(3) A constable may, if they believe on reasonable grounds that

person A has engaged in 1 or more specified acts towards person B and that those acts have caused, or are likely to cause, fear or distress to person B, notify person A in writing that—

(a) the specified act or specified acts done to person B are causing, or are likely to cause, fear or distress to person B; and

(b) engaging in any other specified act towards person B may amount to an offence under section 216Q of this Act.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), if person A has received a notice in writing under subsection (3), person A is presumed to know that—

(a) any specified acts they do to person B after receiving the notice may amount to a pattern of behaviour directed at person B; and

(b) that pattern of behaviour is likely to cause fear or distress to person B.

Section 216O provides the ability for constables to issue what are essentially written warnings to people. After a person (Person A) has been issued with one of these warnings, then they are put on notice that any future communication that they have with Person B (or Person B’s workplace, school, sports team, etc) that causes, or is likely to cause, Person B to feel “distress” could be understood as part of a pattern of criminal harassment or stalking.

This is extremely problematic for several reasons.

Firstly, in 2024 the New Zealand Free Speech Union broke the news that the New Zealand Police have been training their officers to respond to and record incidences of so-called “hate speech” and “non-crime hate incidents”.3 Police were trained to recognise and record a broad range of speech as “hate speech”, even though parliament has not passed any laws to ban such speech.

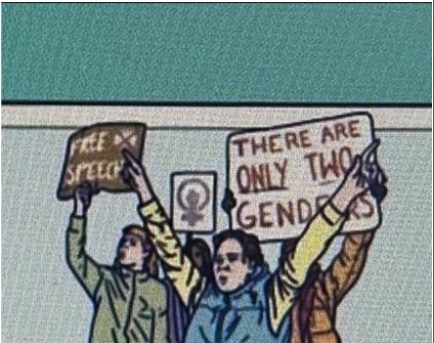

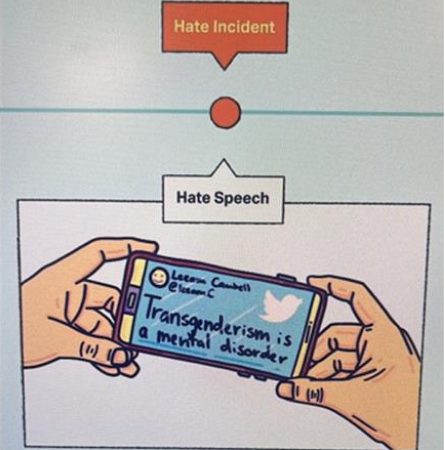

Reproduced below are copies of cartoons that were included in police training manuals as examples of actionable “hate speech”.

It is an undeniable fact that police officers in New Zealand have been trained to view speech that recognises the biological reality of sex and speech that questions

gender ideology as “hate speech” and that this training was on-going until 2024.

Even though these cartoons show examples of legitimate and lawful speech that most New Zealanders either agree with, or do not strongly object to4, police officers have been through compulsory training courses that have trained them to recognise this speech as hateful and harmful.

A police force that has been trained to view any questioning of gender ideology as “hateful” is likely to take a heavy handed and unreasonable approach when issuing written notices under Section 216O(3) and making decisions to prosecute people pursuant to Section 216O(4).

The fact that the New Zealand Police thought it was appropriate to label gender critical speech as “Hate Speech” shows how vitally important it is that New Zealand has good laws that protect our existing rights to freedom of thought, religion and speech.

The Women’s Rights Party submits that the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill as it is currently drafted is not good law, because it does not contain sufficient protections to ensure that ideological bias within the New Zealand Police does not result in a heavy handed and unreasonable approach towards the prosecution of people who question gender ideology, or who cause

“distress” because they do not affirm gender identities when interacting with people have adopted gender identities that do not correspond to their biological sex.

Secondly, if police constables were able to issue 216O(3) notices to women simply because they have caused subjective “distress” to one other person by acknowledging biological reality, then this would have a crushing and chilling effect on free speech. It would trap women and children in unsafe situations, and prevent women from being able to maintain or defend their rights, such as:

- The right to speak freely.

- The right to peaceful assembly, association, and movement.

- The right to safe single-sex spaces for women and girls.

- The right to be free from violence in all its forms.

- The right to protect and safeguard our children.

- The right for motherhood to be recognised as exclusively female.

- The right to fair play in sports.

- The right to use clear and plain language when referring to women in the media, academia, in healthcare, at work and at home.

We can look at a recent real-life example from Scotland and use it as a thought exercise to better understand how the currently worded Amendment Bill would harm women if it was enacted here in New Zealand.

Sandie Peggie is a nurse who was employed at an NHS hospital in Kirkcaldy, Scotland. Ms Peggie was accused of “unlawful harassment” during an employment tribunal case, because she used male pronouns to refer to a biologically male (but transgender identifying) doctor. The tribunal judge said that referring to the doctor using male pronouns could cause him “pain and distress”.

Luckily for Sandie Peggie, she was already in a tribunal setting, with lawyers acting on her behalf, and a good support system around her. She was able to successfully

defend herself against the “unlawful harassment” accusations and was granted permission to use biologically correct pronouns when speaking at the tribunal.

The background to the tribunal case is that Sandie encountered the male doctor in the female changing rooms at Victoria Hospital in Kirkcaldy on three separate occasions.5 Ms Peggie says she felt uncomfortable when the doctor started undressing in front of her while the two were alone in a women’s changing room.

She had previously felt embarrassed when the doctor had been in the changing room at the same time as her. The pair exchanged words, and the doctor complained about Ms Peggie’s behaviour, alleging it was bullying. Ms Peggie was

put on leave and then suspended in January 2024 pending an investigation.6

Sandie Peggie, the Scottish

nurse accused of “unlawful

harassment” for using male

pronouns to refer to a

biologically male doctor.

If a similar situation was to occur in New Zealand under the proposed Amendment Bill, then the male (transgender identifying) doctor could go to the police and claim that he felt “distress” because a woman had told him to leave a female changing room. A police constable could then issue the nurse with a notice pursuant to Section 216O to put her on warning that she was liable to be charged with a criminal

offence – which carries up to a five year jail term – if she complained again to the man7, or tried to prevent him from entering the female changing room8, or if she complained to her colleagues or employer9.

Unlike Sandie Peggie, this hypothetical New Zealand nurse would not have a legal team immediately on hand to advocate for her rights, or strong support and advice from multiple human rights advocacy groups. In almost every case, a New Zealand nurse who was put into this position would feel frightened by the police involvement, and this would have a chilling effect on her ability to advocate for herself and protect her own safety, privacy and dignity. In this hypothetical case, a notice from a police constable pursuant to Section 216O would essentially be a “put up, shut up, and don’t complain again or you will be charged with a serious crime” notice.

Situations where biological men force their way into intimate female spaces such as changing rooms are obviously egregious breaches of women’s safety, privacy and dignity. But women’s rights could easily be extinguished by Section 216O notices in many other ways. They could be used to silence and intimidate women who want to speak out against transgender identifying males playing in their all-female sports team, or joining their breastfeeding support group, or any one of countless other situations where the rights of women are contingent on their ability to acknowledge and speak honestly about biological reality.

To people who take a quick look through the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill, it probably appears that the Bill is intended to help women, and to protect people from stalking and harassment. In fact, the Bill as it is currently drafted10 will likely cause great harm to women, by exposing them to dangerous and exploitive situations where they are persecuted and silenced via the law.

Thirdly, when we look overseas, we can see recent examples of other police forces using similar anti-harassment and anti-stalking legislation to intimidate and silence women who speak truthfully about biology and truthfully about the ways that males impact female spaces and services.

Whether or not these police forces have undergone compulsory “non-crime hate incident” and “hate speech” training like the New Zealand Police force is not known.

But we can see a pattern repeating over and over, all around the developed world, where women who are critical of gender ideology are targeted with prosecution because of their views. And it is important to note that these women are being prosecuted under pieces of legislation that the public think have been developed to protect women from harm.

For example, in Australia a woman called Kirralie Smith was recently served with two apprehended violence orders (AVOs) because of social media posts that she made

about transgender-identified male soccer players who were playing in women’s soccer teams. Smith has never met either of the two males who brought the action.

Australian woman Kirralie Smith, recently served with two apprehended violence orders (AVOs) because of social media posts she made about men playing in women’s soccer teams

An AVO, or Apprehended Violence Order, is an order that prevents a person (the defendant) from threatening, intimidating, harassing, stalking, assaulting, or damaging the property of the ‘person in need of protection’ (PINOP). An AVO works by laying down restrictions that prohibit the defendant, who is the recipient of the order, from engaging in certain conduct that could potentially put the protected

person in danger. These restrictions are commonly referred to as ‘conditions of the AVO,’ which may include forbidding the defendant from assaulting, threatening, harassing, or intimidating the protected person. In this way, an AVO can be seen as a legal measure to safeguard individuals from physical or mental harm. They are imposed when an individual has fears and there are reasonable grounds to fear

harm to their well-being or safety11.

When reporting on this case, the Australian Human Rights Law Alliance commented that “the treatment of Kirralie Smith is part of a pattern whereby activists exploit the legal system to shut down debate and silence those with whom they disagree”.

The Human Rights Law Alliance reports that the police became involved simply based on Smith’s online speech about transgender ideology – with no physical violence involved at all and they comment: “It is deeply troubling for freedom of conscience and freedom of speech in our country if emails and social media posts that contain no element of threat or harassment can justify police intervention.”12

In Scotland, Marion Millar was charged with posting “transphobic” tweets that purposely caused “distress or anxiety”. She was charged under the Malicious Communications Act – which makes it illegal to send or deliver articles that purposely cause “distress or anxiety” – for posting “transphobic” and “homophobic” tweets. The mother of two faced up to two years in jail if she was convicted13.

One of the tweets investigated by police showed a photograph of a bow of ribbons tied around a tree. The ribbons were green, white and purple to represent the Suffragette movement. A complaint was made to the police suggesting that the ribbons represented a noose. For this and other tweets Millar was charged with “threatening or abusive behaviour”14. Although the charges were later dropped, they caused a lot of stress for Millar and her family, and this kind of prosecution has a chilling effect on free speech, especially free speech related to gender critical views and women’s rights.

Scottish woman Marion Millar charged under the Malicious Communications Act – charges that were later dropped.

Speaking during the case, a For Women Scotland spokesperson said: “Marion is naturally upset that the police have decided to press ahead with charges. Sadly, in Scotland, it seems both free speech and women’s rights are under attack. Too many people mistake credible, open threats of violence (to which women are well used) with hurt feelings.”15

Point 3

The belief that human sex or gender is changeable has only risen to prominence in New Zealand within the last decade or so. Despite the best efforts of the media and pressure groups to promote gender ideology, the belief that humans can change sex or gender is still widely rejected in New Zealand.

Recent research carried out by the Pew Research Center in America found that 65% of American adults think that a person’s gender is determined by sex at birth. In 2022, the same research centre found that 38% of American adults thought a person’s sex did not determine whether they were a man or a woman. By 2024, that figure had dropped to just 33%.16 This indicates a sharp drop in public support for

gender ideology in America over the last couple of years.

No comparable research has been carried out in New Zealand. However, recent polling commissioned by Family First and surveyed by Curia Market Research found that 69% of respondents opposed gender ideology being taught in primary schools. A 2023 poll found that just 13% of respondents agree that “boys who identify as girls be allowed automatic right of access to girls sports teams”.

This is a significant drop from a similar poll in 2018 in which 38% of respondents agreed. A 2021 poll found that only 22% of respondents think boys who identify as girls should be allowed automatic access to girl’s toilets and changing rooms and almost two in three (61%) disagree – a much stronger opposition than in a similar poll in 2019 which found that 46% v 36% said that biological sex should trump gender identity.

And a nationwide poll found significant opposition to a decision which resulted in a teacher losing his teaching licence for refusing to use a student’s preferred pronouns. Only 16% of respondents thought that a teacher should lose their licence for “misgendering” a transgender identifying student17.

Despite the lack of public support for gender ideology, and indications that public support for gender ideology is dropping rapidly, there have been various attempts to enshrine gender ideology into the laws of this country, including during recent reviews of the Human Rights Act. We consider that the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill is another attempt to enshrine gender ideology within New Zealand law, and to force women to comply with gender ideology to the detriment of their safety, privacy, established freedoms and wellbeing.

Many people who believe that they have transformed their own sex, or gender, into another sex, or gender, feel “distress” when ordinary people use biologically correct language to describe their sex. The Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill would create a legal minefield for ordinary New Zealanders who encounter transgender-identifying people in their workplaces, schools, and social

settings. Ordinary New Zealanders face the risk of prosecution and up to 5 years of jail time simply for speaking honestly about biological reality, or about gender ideology, in ways that most people consider to be reasonable.

Recommendation

Amend Section 216O of the Amendment Bill to define stalking and

harassment as follows:

(1) For the purposes of section 216Q, a person (person A) stalks and harasses another person (person B) if person A—

(a) engages in a pattern of behaviour that is directed at person B by doing any specified act to person B on at least 3 2 separate occasions within a period of 12 months; and has a serious effect on B.

(b) A’s behaviour has a “serious effect” on B if—(b) engages in that pattern of behaviour knowing that it is likely to cause fear or distress to person B

(i) it causes B to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against B, or persons associated with B; and/or

(ii) it causes B serious alarm which has a substantial adverse effect on B’s usual day-to-day activities.

(2) To avoid doubt, the specified acts may be the same type of specified act on each separate occasion, or different types of specified acts.

In addition, amend Section 216O of the Amendment Bill as follows:

(3) A constable may, if she/he believes on reasonable grounds that person A has engaged in 1 or more specified acts towards person B and that those acts have caused, or are likely to have caused a serious effect on person B as defined in (1)(a), notify person A in writing that—

(a) the specified act or specified acts done to person B are causing, or are likely to cause, fear or distress to person B B to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against B, or persons associated with B; and/or

(ii) it causes B serious alarm which has a substantial adverse effect on B’s usual day-to-day activities.

; and

(b) engaging in any other specified act towards person B may amount to an offence under section 216Q of this Act.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), if person A has received a notice in writing under subsection (3), person A is presumed to know that—

(a) any specified acts they do to person B after receiving the notice may amount to a pattern of behaviour directed at person B; and (b) that pattern of behaviour is likely to cause fear or distress to have a serious effect on person B as defined in (1) (a) and (b).

- https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/make-a-submission/document/54SCJUST_SCF_BDB818E0-3135-

4D91-E700-08DD18052784/crimes-legislation-stalking-and-harassment-amendment ↩︎ - This point is expanded on page 10 ↩︎

- www.fsu.nz/thought_police_we_really_need_your_help ↩︎

- This point is expanded on page 10 ↩︎

- https://freespeechunion.org/nurse-wins-right-to-refer-to-transgender-doctor-as-male-in-legal-battle/ ↩︎

- https://www.thecourier.co.uk/fp/politics/5159430/nhs-fife-trans-row-tribunal/ ↩︎

- Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill, section 216P(1)(a)(iii) ↩︎

- Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill, section 216P(1)(a)(i) ↩︎

- Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill, section 216P(1)(a)(v) ↩︎

- And particularly considering the compulsory Police “hate speech” and “non-crime hate incident” training that was continuing up until 2024 ↩︎

- https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e39cf93e-4a8d-4e51-9279-b4e767452113 ↩︎

- www.hrla.org.au/campagner_for_biological_truth_served_with_avo ↩︎

- www.nationalreview.com/corner/british-woman-may-find-herself-in-jail-over-transphobic-tweets/amp/ ↩︎

- www.spiked-online.com/2021/10/28/the-shameful-treatment-of-marion-millar/ ↩︎

- https://thegaurdian.com/uk-news/2021/jun/04/gender-critical-feminist-charged-over-allegedly-trasnphobic-tweets ↩︎

- https://www.pewresearch.org/topic/gender-lgbtq/ ↩︎

- https://familyfirst.org.nz/2024/05/15/media-release-opposition-to-puberty-blockers-gender-ideology-

for-children-poll/ ↩︎