Submission in response to the Ministry of Health’s Consultation on Safety Measures for the Use of Puberty Blockers in Young People with Gender-related Health Needs

Tēnā koutou

This submission of the Women’s Rights Party of Aotearoa New Zealand is in response to the Ministry of Health’s Consultation on Safety Measures for the Use of Puberty Blockers in Young People with Gender-related Health Needs1

Introduction

The Women’s Rights Party is a registered political party focused on issues that directly impact women, girls, and children. Our primary concern is protecting the rights of women and children. It is in this context that we provide input as an organisation representing around 800 members and others in the wider community who are concerned at the lack of safety measures in place to protect children and adolescents from inappropriate use of the hormones known as “puberty blockers” (Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues) to treat conditions related to “gender distress”.

In our submission we note the lack of good quality evidence that such use is either safe or effective. We will refer to the extensive independent, peer reviewed and systematic review of the safety and efficacy of puberty blockers conducted over four years and submitted by Dr Hilary Cass, Chair of the Review, to the National Health Service England in April 2024.2

We will discuss the effect of gender medicine on lesbian, bisexual and gay children.

We will contest the view that children are being discriminated against if their access to puberty blockers is restricted.

Finally, we will discuss the issue of consent as we are talking about children and minors in this case. By way of definition, we regard children as those who are pre-pubescent and adolescents as those under 16 years of age.

Language

It should be noted that in this submission we use terms relating to “gender” or “gender identity”; language that is heavily contested. The Women’s Rights Party describes “gender” as an imprecise concept that refers to sex-based stereotypes and social expectations, e.g. what is considered feminine and masculine.

“Gender identity and expression” refer to the identification with, and expression of these sex-based stereotypes. Such stereotypes have historically been used as a tool of oppression of women and girls, and continue to be so. Therefore the rights of women and children to reject these stereotypes without discrimination, labelling, or medical intervention to “fix” them is paramount.

“Gender incongruence” is the term used to describe clinically significant distress and functional impairment resulting from a-typical expression of sex-based stereotypes and one’s biological sex. Previously associated predominantly with young boys, this may persist into adulthood and the boys grow up to be gay or bisexual.

“Gender dysphoria” is a term used in research publications and clinical settings. It is a label commonly used to describe feelings, but it is also a formal diagnosis described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

In our submission, we use the term “gender-related distress” to include both “gender incongruence and dysphoria”, acknowledging that such distress is real for those involved, but is typically experienced along with other issues such as ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorders) and body dysmorphia, which may also be expressed as eating disorders and self-harming.

The case against off-label use of puberty blockers

The Women’s Rights Party has previously called on the Ministry of Health to ban the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for children and adolescents experiencing gender-related distress.3 It should be noted that puberty blockers are licensed only for use in young children (for precocious puberty) or older adults (for certain cancers). Use of puberty blockers for gender incongruence or dysphoria is not currently licensed.

In the Ministry’s consultation document, questions are asked as to whether additional safety measures are needed, whether prescribing should be further restricted, whether young people with gender-related health needs should be able to receive this treatment if prescribing is further restricted, and what impacts there could be from additional safety measures.

Licensing of medicines requires a robust assessment of safety and effectiveness data. These medications have not undergone that process, which means the safety and risk implications for use with gender dysphoria have not been assessed.

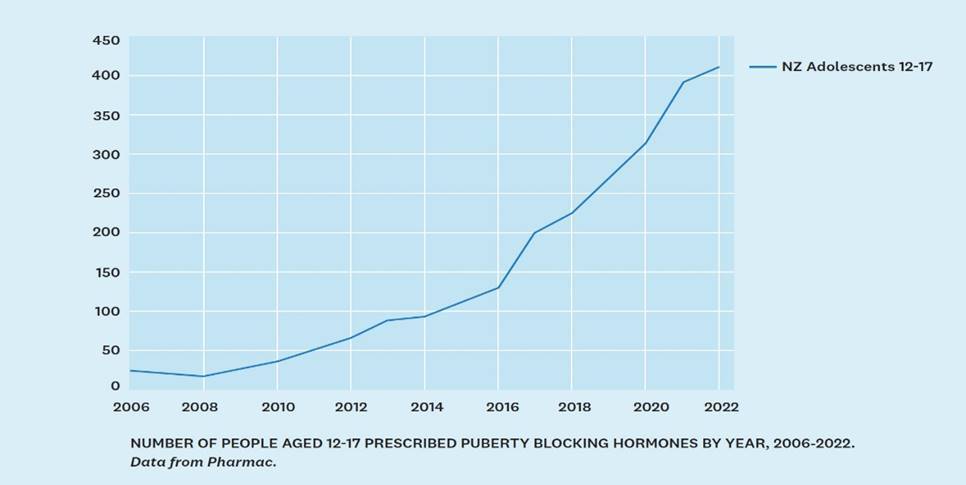

Thus, prescribing puberty blockers in this context is unrestricted as it is off-label and there are no safety measures in place. Despite this, Pharmac data that excludes young children and older adults (i.e. includes only 12-17 year olds) shows an alarming increase in the use of such medicines, which can only be off-label to treat patients presenting with gender-related distress.

In New Zealand, prescription of puberty blockers for gender dysphoria started around 2011; prevalence of use increased to 2014, then more steeply to 2022, followed by a decline. Compared to the Netherlands (which started prescribing in the 1990s), New Zealand had 1.7 times the cumulative incidence of first prescriptions by 2018. Compared to England and Wales up to 2020, New Zealand had 3.5–6.9 times the cumulative incidence.4

In March 2024 the National Health Service England banned the routine use of puberty blockers after a four-year independent review commissioned by the NHS and chaired by eminent paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass, concluded in its Interim Report that there was insufficient robust evidence that puberty blockers are safe to take or clinically effective to treat “gender dysphoria”.5

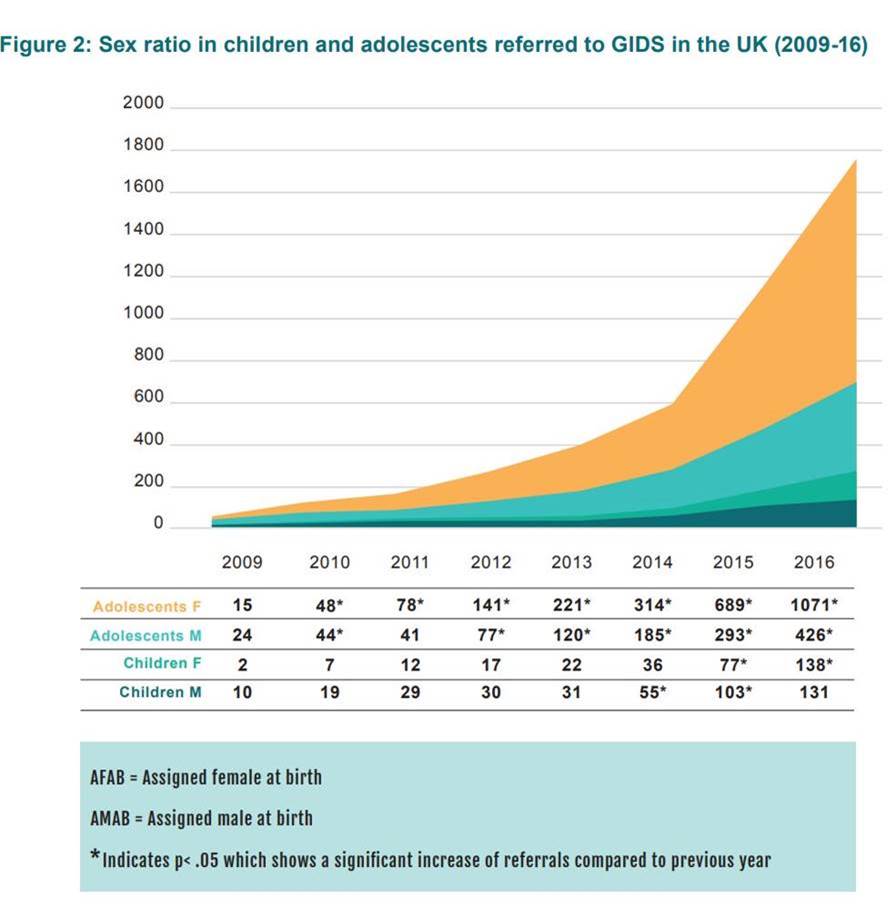

The final Cass Report noted the pattern not only of the rising number of children presenting to the UK NHS Gender Identity Service (GIDS), which has been increasing each year since 2009 with an exponential rise in 2014. This trend is also consistent with the experience in New Zealand as reported above.

Clinicians have also reported a change in the case-mix of the young people seeking support. Cass notes that this shift is consistent with other Western countries.

This shift is of significant concern to the Women’s Rights Party. It is remarkable that there has been so many more birth-registered females being referred in adolescence, and a sharp increase in prescribing puberty blockers, which marks a shift from the cohort that these services have traditionally seen; that is, birth-registered males presenting in childhood, on whom the previous clinical approach to care was based.6

Cass reported that at the time GIDS was established in 1989, clinicians saw fewer than 10 children a year, predominantly pre-pubertal birth-registered males. The main focus was therapeutic, with only a small proportion referred for hormone treatment by around age 16.7

“The approach to treatment changed with the emergence of ‘the Dutch Protocol’ which involved the use of puberty blockers from early puberty. In 2011, the UK trialled the use of puberty blockers in the ‘early intervention study.’ Preliminary results from the early intervention study in 2015-2016 did not demonstrate benefit. The results of the study were not formally published until 2020, at which time it showed there was a lack of any positive measurable outcomes.”

Despite this, Cass reports that from 2014 puberty blockers moved from a research-only protocol to being available in routine clinical practice and were given to a broader group of patients who would not have met the inclusion criteria of the original protocol, notably adolescent girls.

As we will discuss later, this should have been of considerable concern in light of follow-up studies dating as far back as 2008, before widespread use of puberty blockers for gender distress, showing that childhood criteria may “scoop in” girls who are unlikely to persist with gender dysphoria into adulthood, and are more likely than the general female population to be lesbian or bisexual.8

Cass reports that the adoption of a treatment with uncertain benefits without further scrutiny is a significant departure from established practice. This, in combination with the long delay in publication of the results of the UK trial, has had significant consequences in terms of patient expectations of intended benefits and demand for treatment.

In light of the Interim Report, the Ministry of Health delayed its own review of the evidence of the safety, effectiveness, and reversibility of puberty blockers, and announced a further delay on release of the final Cass Report in April 2024.

At the time, the Women’s Rights Party urged the Ministry to immediately take on board the findings of the damning final Cass Report, which found young people had been given life-changing treatment despite “remarkably weak” evidence of safety or effectiveness.9

New Zealand health authorities continue to be out of step with European countries such as Sweden, Finland, and France, as well as the NHS England, where the drugs are now limited to clinical trials. Scotland also paused the use of puberty blockers for under 18-year-olds in direct response to the Cass Report.10

The Cass Report found that that existing studies were of poor quality and lacked evidence on the long-term impact of taking hormones from an early age, and recommended a pause on prescribing blockers in light of the potential short and long-term side effects, including menopausal symptoms, weaker bone density and the potential impact on fertility, sexual function and brain development.

Dr Cass concluded that the research had let all those involved down, and most importantly children and young people. Far from giving children “time to think”, the Cass Report found that puberty blockers effectively locked them into a medical pathway leading to cross-sex hormones and surgeries that are irreversible.

Effect of gender medicine on sexual orientation

Of particular concern is the impact of puberty blockers on lesbian, gay and bisexual children. Puberty blockers and wrong sex hormones are designed to give children and adolscents the appearance of being the opposite sex, and of being heterosexual.

On the other hand, children presenting with a-typical fantasies and behaviours that do not align with societal sex-role expectations, who are allowed to grow up naturally and experience puberty, will in the vast majority of cases, grow up to be comfortable with the sex they are; many of them lesbian, gay or bisexual.

The link between children presenting with gender-related distress and sexual orientation has been reported in multiple longitudinal studies for years.

In just one example, a 2008 study provided information on the natural histories of 25 girls diagnosed with gender identity disorder (GID). The girls were followed up 12 years after diagnosis. Only three (12%) continued to experience gender dysphoria. A majority (56%) were classified as bisexual/homosexual. The remaining participants were classified as either heterosexual or asexual.11

Another study concluded that most children with gender dysphoria will not remain gender dysphoric after puberty. And with regard to sexual orientation, the most likely outcome of childhood gender identity disorders was found to be homosexuality or bisexuality. 12

New Zealand health authorities lack of leadership

It is our view, as the Women’s Rights Party, that New Zealand health authorities have been held hostage to a vocal minority who have put our children’s health at risk of lifelong irreversible damage.

We note that at one stage, the Ministry of Health quietly removed a claim from its website which stated that puberty blockers were “safe and reversible”, yet the Ministry continued to prevaricate on its duty to provide leadership across the health system.

Further, Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora contracted PATHA (the Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa), to update its guidelines for “gender-affirming care” for healthcare professionals in New Zealand, despite the Cass Report assessment of guideline quality which put the New Zealand PATHA guidelines second to last – a very low score of 149/600.

The Cass Report strongly supported a holistic approach that looks at other conditions often found in young people presenting with “gender distress”, including ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder), eating disorders, and sexual abuse. The Women’s Rights Party supports this approach. As Cass reported: “Puberty is an intense period of rapid change and can be a difficult process, where young people are vulnerable to mental health problems, particularly girls. Unwelcome bodily changes and experiences can be uncomfortable for all young people, but this can be particularly distressing for young neurodiverse people who may struggle with the sensory changes.”13

The Cass Report acknowledged the role of social influences on young people, including on-line pornography, social media, and peer pressure. The Report pointed out that “social contagion” may explain, at least in part, the exponential rise in the number of teenage girls being referred to gender services.14

In an interview with Emeritus Professor Charlotte Paul of the University of Otago, Dr Paul also noted that what started in the 1990s in the Netherlands as concern about trying to treat a very small group of mostly pre-pubescent boys presenting with “gender incongruence” is now more likely to be girls experiencing psychological distress with the onset of puberty, who are more likely to have co-existing autism or mental health problems.15

In light of the failure of the Ministry of Health to act, even after the release of the final Cass Report, the Government has tasked the Ministry of Health with consulting on whether there should be additional safety measures for puberty blockers, such as regulations under the Medicines Act.

In a December 2023 article in North and South16, Dr Paul noted that the European approach to regulation of puberty blockers had been through the health authorities, thus removing the issue from the political realm. The appropriateness and safety of hormonal treatments for children and young people was evaluated according to the norms of medical practice.

This is in sharp contrast with the US where health agencies have been notably reluctant to discuss the possibility of harm, and the issue has become deeply political. In 22 States there are now legal bans on hormones or surgery for anyone under the age of 18 – bans that have been challenged all the way to the US Supreme Court and look likely to stay in place.17

Dr Paul states that the involvement of political parties in enacting laws to regulate medical practice could fuel partisan animosity: greater discrimination against trans people on the one hand, and greater uncritical affirmation of hormones and surgery for trans-identified youth on the other.

By contrast, Dr Paul stated that if health agencies act according to professional norms and standards to prevent harm to children, there would be less reason for hostility on either side.

Instead, the Ministry extended its current consultation to vested interests which promote puberty blockers in the context of “gender-related” treatment. We note that the Ministry is particularly seeking input from organisations that represent people who may be affected by safety measures – those providing gender medicine services and those receiving such services.18

This suggests that the Ministry is not basing its advice on medical and professional evidence, despite that fact that Ministry’s own Evidence Review found a lack of good quality evidence for the effectiveness or safety of puberty blocking treatment in young people with gender dysphoria.19 The Evidence Brief concluded that: “We do not have good evidence to say that the medicines used improve the longer-term outcomes for young people with gender-related health needs – nor that the potential longer-term risks are low.”

This is a convoluted way of saying the current practice of prescribing puberty blockers could well be doing more harm than good. The Women’s Rights Party position is that the Ministry has put New Zealand children at risk by continuing to allow “off-label” prescribing of puberty blockers at far higher rates than other similar countries.

These hormones suppress normal puberty with the aim of relieving suffering and improving final physical outcomes for those wanting to transition away from their birth sex. However, Dr Cass concluded that the research has let all those involved down, and most importantly children and young people.

As Dr Paul said: “What started as a sympathetic stance towards a tiny number of children with lifelong gender dysphoria (distress resulting from incongruence between one’s birth sex and experienced gender) has grown beyond recognition. The context is new: the idea that everyone has a “gender identity” (an inner sense of being male or female or non-binary) that overrides biological sex.”20

In his interview with Dr Paul, long-standing journalist Sean Plunket described New Zealand’s high rate of prescribing puberty blockers to children as the “biggest medical scandal since the “Unfortunate Experiment” at National Women’s Hospital”21

Dr Paul explained that the field of gender medicine had moved swiftly and well ahead of the evidence and the norms of medical practice, i.e. acting in the best interests of the patient; being cautious about prescribing unapproved medicines; assessing a patient’s condition before prescribing; assessing the capacity for patient to give consent (noting we are talking about children); and the responsibility to provide accurate and balanced information and saying when clinicians simply do not know because of a lack of reliable evidence.

What got left behind was the best interests of the children. Dr Paul argues that the current approach, breaches the above accepted norms of medical practice and Medical Council standards in New Zealand.

Dangers of a rights-based approach

In a recent NZ Herald opinion piece, Dr Paul quoted Professor Paul Hofman and colleagues of the University of Auckland’s Liggins Institute, who have examined healthcare practices internationally. They conclude that, over time, “guidelines across different countries were progressively shaped by a rights-based approach that removed previous safeguards and increased availability of gender reassignment medical interventions of children and adolescents.”22

In a recent Substack article,23 Resist Gender Education (RGE) points out that those who advocate for continued easy access to puberty blockers have condemned the possibility of restrictions on the basis that regulating the suppression of puberty is against the human rights of children and discriminatory against “transgender children”, who desperately “need” this medication. These proponents claim that denying use of this medication to a particular group based on their gender identity is sex-based discrimination which is illegal under the Human Rights Act.

However, as RGE points out, “regulations restricting puberty blockers would not be made on the basis of sex or gender identity but on the basis thatthey do not provide the benefits promised.The regulations would protect all children from the current unsafe prescribing environment”.

RGE goes on to point out that when puberty begins at a very early age it is a medically necessary intervention to delay its effects on bone growth and height. After a short period of use, the medication is ceased and a natural puberty resumes. Patients become fully-functioning, fertile women. In contrast, puberty blockers are used to avoid puberty altogether, with lifelong, largely unknown consequences, including possible sexual dysfunction and infertility.

It is already proven that puberty blockers prevent the genitalia of boys from growing to adult size and the hips of girls from widening enough for childbirth. Sterility, osteoporosis, early menopause, and organ failure are all known potential side effects when puberty blockers are followed by wrong-sex hormones, as happens in almost 100% of cases.

Further, one of the most fundamental rights that belongs to children is the right to go through a natural puberty that allows them to develop the cognitive maturity needed to give proper consideration to their identity, as adults.

Prescribing children puberty blockers denies potentially gay, lesbian and bisexual children their human rights to experience and express their sexual orientation as adults.

The effects of puberty blockers combined with wrong sex hormones in fact, deny all children their right to grow up and to experience their full sexuality, They also deny these children their rights to their reproductive capacities when they grow up.

Says RGE: “We are talking about children here, not the euphemistic term, ‘young people’. Puberty for girls often starts at 10-11 years and for boys at 12-13 years. These children are too young to begin to understand the consequences of halting their natural brain and body development. Allowing unregulated access to puberty blockers under the pretext of “equity” is placing unevidenced ideological beliefs above best medical practice.”

RGE concludes: “It is not discriminatory to want the best for our children and to ethically restrict the availability of drugs that target their developing bodies and minds. All children should be given the same opportunity to grow up unhindered by drugs that are not proven to be safe or effective.”

Issue of consent

The Charter for Healthcare Services in Aotearoa New Zealand states children have the right to participate in decision-making and to be kept safe from all harms.

We agree that patients have a right be consulted about medical decisions when they are old enough to understand the consequences of their decisions. In the case of puberty blockers, children cannot give informed consent because even the Ministry cannot vouch for their efficacy or safety. It is the Ministry of Health’s responsibility to step in on behalf of children and keep them safe from all harms.

Prescribing puberty blockers to children simply because they want them is a practice unique to transgender medicine. In all other treatments, medication is prescribed because it is known to be effective and the subjective feelings and beliefs of the patient are not treated as more important than clinical evidence.

The Women’s Rights Party submits it is unethical for puberty blockers to remain unregulated in New Zealand, allowing children to access a medicine that disrupts their physical and cognitive development and is being pushed to them in a social contagion.

Children also cannot give informed consent because, as children, they have no capacity to understand what it would be like to lose their sexual and reproductive capacities as adults. Where informed consent is not possible, it is acceptable for regulations or legislation to keep children safe, including from their parents!

The affirmation treatment for “gender dysphoria” is unique in that life-altering drugs are being given to children, simply on the basis of their subjective feelings and beliefs. In no other branch of medicine do clinicians defer to the patient’s request without investigating the cause of the distress or trying less invasive treatments first.

It is completely unethical that a medication that deliberately eliminates the crucial physical and cognitive development of puberty is available without regulation in New Zealand, and has been allowed to gain a celebrity status amongst children, and in some cases, their parents.

We have laws against child marriage, even if condoned by parents, because children are too young to consent to such a consequential decision. Similarly, we need strict regulation against puberty blockers being used to eradicate puberty, even if parents believe they have a transgender child who “needs” such medication.

Just as we have laws against child marriage, because children are too young to consent to such a life-changing decision, we need strict regulation of puberty blockers against their use in the context of gender-related issues, even if parents are demanding these unevidenced interventions.

- Consultation on safety measures for the use of puberty blockers in young people with gender-related health needs ↩︎

- Cass, H. Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People: Final Report. April 2024 ↩︎

- Ovens, J. Media release, April 18, 2024. ↩︎

- Paul, C, Tegg, S. & Donovan, S. “Use of Puberty blockers for Gender Dysphoria”. NZ Medical Journal, 27 September 2024 ↩︎

- Cass, H. Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People: Interim Report. February 2022 ↩︎

- Cass, H. Final Report, p24 ↩︎

- Cass, H. Final Report; p25. ↩︎

- Drummond, K. et al. Journal of Developmental Psychology, January 2008; 44(1), pp35-45. ↩︎

- Ovens, J. “Health Ministry Should Ban Puberty Blockers”. 18 April 2024 ↩︎

- Scotland’s under-18s gender clinic pauses puberty blockers ↩︎

- Drummond, K. et al. Journal of Developmental Psychology, January 2008; 44(1), pp35-45. ↩︎

- Wallien MS, Cohen-Kettenis PT.J Journal of the American Academy of Childhood Adolescence Psychiatry. December 2008; 47(12), pp1413-1423 ↩︎

- Cass, Final Report, p. 122 ↩︎

- Cass Final Report, p.117 ↩︎

- Plunket, S. Interview with Emeritus Professor Charlotte Dr Paul ↩︎

- Paul, C. North and South, December 2023 ↩︎

- United States v. Skrmetti. SCOTUSblog, 4 December 2024 ↩︎

- Ministry of Health. Consultation on Safety Measures for the Use of Puberty Blockers in Young People. 21 November 2024 ↩︎

- Ministry of Health. Impact of Puberty Blockers in Gender-Dysphoric Adolescents: An Evidence Brief. 21 November 2024. ↩︎

- Plunket, S. Interview with Emeritus Professor Charlotte Dr Paul ↩︎

- Plunket, S. Interview with Emeritus Professor Charlotte Dr Paul ↩︎

- Paul, C. “Where do we go now with Puberty Blockers?” NZ Herald, 7 January 2025 ↩︎

- Resist Gender Education, 9 January 2025 ↩︎